I begin with a digression, because I must share this.

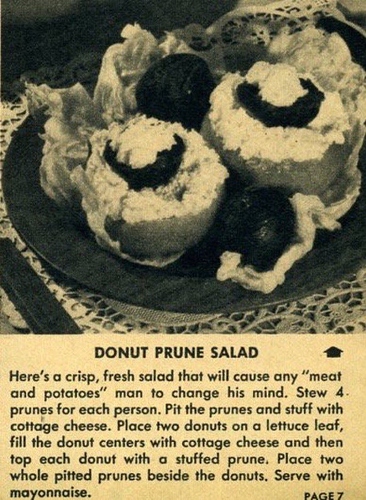

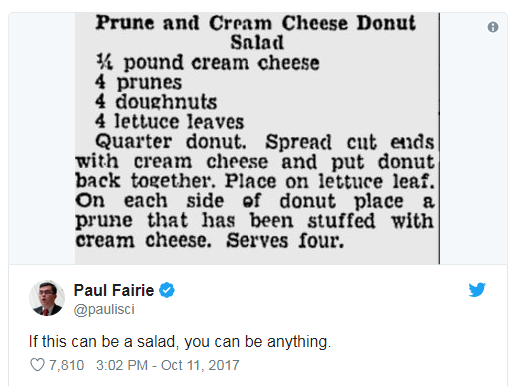

I mean. Once you have combined the concepts of “donut”, “prune” and “salad” into a single dish, why not serve it with mayonnaise?

What gets me here is the apparent random anarchy of the ingredient choices, paired with the strictly limited, generic, whitebread pool of possible ingredients that must have been drawn from. There are no spices or seasonings, nothing that would indicate a culture — except we all know it’s got to be “American, white, 1950-1975.” It’s almost mechanical, like it was created with a very crude randomization algorithm that lacks the finesse and charm of a neural network recipe.

I appreciate how this one (brown) leaves certain factors — not least, all of the actual preparation instructions — up to the cook’s improvisational judgement, so that each performance is unique. John Cage would approve.

Maybe the weirdest thing about the donut prune salad recipe is that it’s not unique. Coincidence or conspiracy?

The aesthetics of the first one, such as they are, seem a little better but I’d honestly rather 86 the mayo and use cream rather than cottage cheese. I’d also rather break my left arm than my right arm.

And in fact yes, I have added “Donut Salad” to my list of potential song titles, but under the category of “probably will never use.”

Anyway, what I was going to write about: I’m currently reading DJ Spooky’s Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture and it’s thrown some provoking thoughts my way. One of them is the idea that our primary mode of thinking is a visual/spatial one, with a coordinate grid, objects that take up space, and the spaces between them. The argument is that this spread in Western thought during the Renaissance with Descartes, the printing press, explorers and maps, etc. It’s probably not much of a stretch to say that movies, television and computers were heavily influenced by, but also strongly reinforced, this spatial paradigm.

It all seems very rational, scientific, and straightforward. Of course, it’s pretty wrong and/or useless at the quantum level, or when considering energy, or for a lot of metaphorical or magical uses, but it’s pervasive and sometimes we try to make things fit anyway. My career has been based on it — 3D graphics and modeling for games and then engineering.

I will speculate with some confidence that the previous mode of thought for most people for most of human history was a bit less spatial and more narrative. When we say “myth” now, unfortunately there’s usually a connotation of falsehood, disdain for the primitive etc. rather than the understanding that the idea of truth itself wasn’t necessarily so fixed and binary.

But steering a little more toward the inspiration from the book: the idea of an “acoustic” mode of thinking, where the measurement of space is more vague, and reality is inhabited by an infinity of interpenetrating fields of energy and motion, pressure and density, transmission and absorption and reflection. There are no distinct “objects,” just a whole where any divisions one makes are arbitrary slices of a spectrum that we know we could have sliced up differently. This ties back into what Curtis Roads was talking about when he claimed electronic music removes dependency on notes.

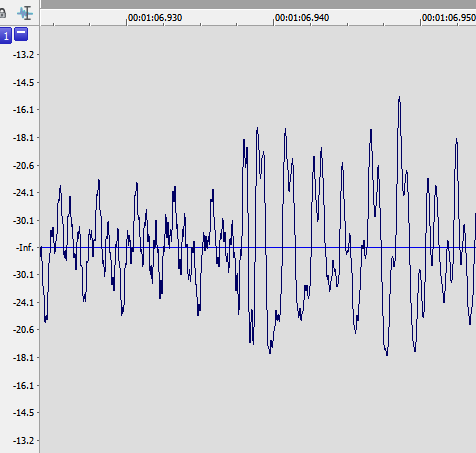

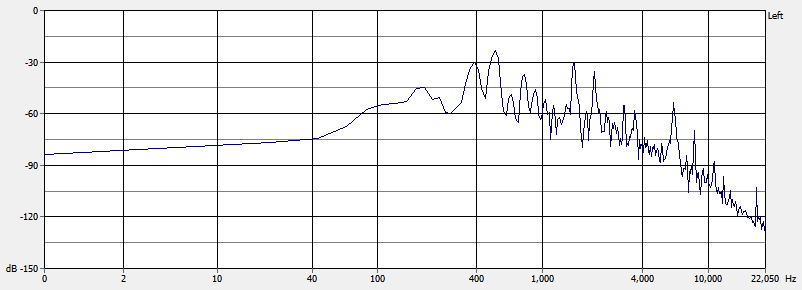

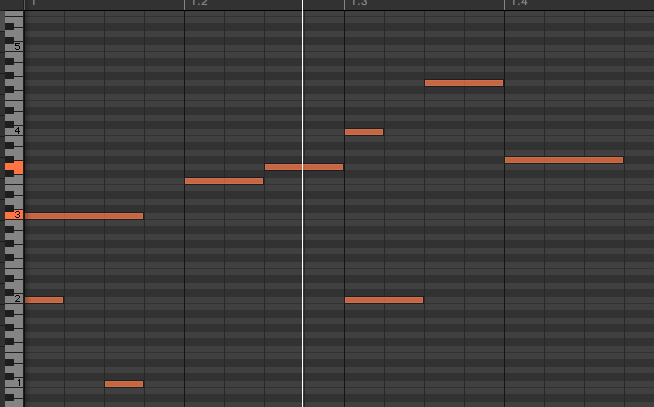

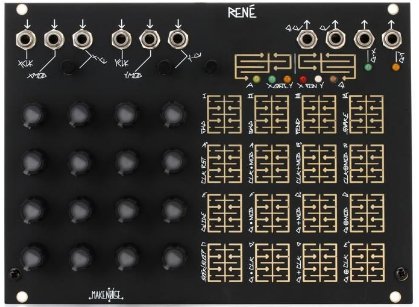

Of course, we still have a tendency to think of sound in terms of grid coordinate systems:

Grids are certainly a useful paradigm, in music and outside it. But it is also very much worth simultaneously thinking about all those overlapping, permeating, permeable fields of energy. Blobs rather than objects. Sounds, rather than notes. Salads, rather than donuts and prunes (sorry). Not just in terms of music and sound, but whatever else may apply. Personal relationships, memes, influences, cultures, societies? Economies, ecologies? Magic, mysticism? In a sense, I think this “acoustic” view of a universe is closer to the narrative one than the visual view is. (And there’s that word “view”, illustrating the bias… and oh we’re illustrating now, also visual…)

Using some of those grid-based tools above, I did some editing this evening of a recording I’d made earlier. There was a point where a feedback-based drone fell into a particular chord, which I thought made a much nicer ending than what happened later. So I took a bit of that ending, ran it through the granular player in the ER-301 to extend it for several seconds, resampled that and smoothly merged it back into the original audio — one continuous drone. No longer two things spliced, nor five thousand overlapping grains of sound; those metaphors stopped being useful, just like eggs stop being eggs when they’re part of a cake.