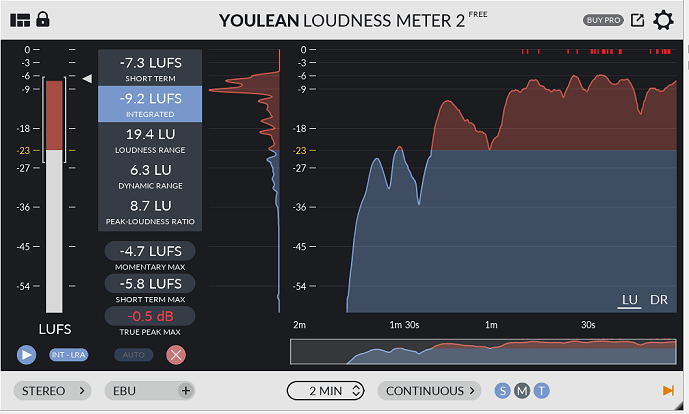

I spent much of my weekend mastering four tracks from Vultur Cadens. Just as important as the specific things I learned: I’m more invested in the result, and have the goal of making my own mastering as consistent as possible with that of an experienced professional. It’s a challenge, but I’m very happy with the results I’m getting so far.

Nathan Moody was a guest recently at the Velocity synth gathering in Seattle, and gave a talk on “Mixing Modular Music” — which includes and complements the advice he gave me about my mixes.

Trying not to make this too long and technical, here are the things I’ve learned that I’m applying now:

- It’s important when using a spectrum analyzer to set the block size high to detect infrasonic content that needs filtering out. Voxengo Span at a block size of 8192, and minimum frequency of 5 Hz, will do the job.

- Stereo phase correlation matters even if you’re not cutting vinyl. Voxengo Span and Correlometer are easy to read: 0 to +1 is good, anything more than brief dips below 0 is bad. Toneboosters EQ4 is an excellent mid-side EQ that can correct it — after a few hours of struggle I’ve found a set of techniques that not only fixes these issues, but often results in a better sounding stereo field. I don’t necessarily care about “natural” here and I’m not aligning multiple microphones, so what I’m learning for myself doesn’t necessarily apply to every mix.

- Fixing big resonances. Something that makes some synth sounds harsh and strident (with both the Lyra and with feedback-based synthesis), and leads to listener fatigue, is frequencies that are really loud compared to the rest of the spectrum. Often bringing them down just a little bit makes them sound great — and then subsequent compression and limiting might mean having to shave them again. Again, EQ4 is great for targeting these. For my purposes, finding these manually and fixing them once they’re already recorded is fine.

- Compression: this can be complex, subtle and subjective. I’m just loosely imitating what Nathan Moody said he did, mostly with Klanghelm MJUC or NI Solid Bus Comp so far, tweaking until I feel like it’s doing something positive. If I were mixing a rock band or making techno or hip-hop there might be more of a system to it. I still feel I have a lot more to learn here.

- With limiting, I still rely on Toneboosters Barricade and Bitwig’s peak limiter for ease of use, transparency and simplicity. But I have a new favorite preset as a starting point in Presswerk.

- In terms of other flavor/vibe/etc. I find I really like u-he Uhbik-Q for flavor EQ. For saturation though, I am still very much “try things at random to see what works, if anything.” Another area where I want to learn more — I hope to someday find a favorite secret sauce, and/or recognize what to use without needing as much experimentation every time.

- Overall I find myself bouncing between Bitwig Studio and Sound Forge Pro 13 for mastering. The former is better for chains of plugins — the effects and the analyzers to monitor them, or EQ that wants tweaking because I tweaked a compressor. The latter has a few handy tools (dynamics statistics, some noise/crackle removal options, and easy fade in/out and crossfading of effects).