I’m diabetic and on three different injectables: a once-a-week Ozempic (blood sugar control was the primary purpose of this drug long before it trended for weight loss), once a morning slow-acting insulin, and pre-meal fast-acting insulin.

All of these use pen needles rather than syringes — the medication is in a “pen”, and you screw on a small single-use needle, dial in the dose, poke yourself with it and hit a button. Painless most of the time, but a hassle (in addition to the process and supplies, the pens require refrigeration until first use), and expensive in America even with insurance.

When you’re done, you slip the safety cap(s) back on, unscrew the needle and throw it into a sharps container. But what if you’re not at home? A coin pocket in jeans, if you have it, can hold ONE used needle in its safety cap, but beyond that…

The Good

BD used to make a “SafeClip” device about the size of a thumb. It was great, clipping off the needle and storing hundreds of them safely inside itself, lasting for many months of regularly going out. And they were about $5 each.

A few years ago they were discontinued. Old stock lasted a while, but eventually sold out. Clones appeared on the market at $45 per clipper…

The Bad

I got a box of 5 pocket sharps containers before our TN/SC vacation. All plastic, about the size of 5 SafeClips, it fills a (men’s) jeans pocket and the needles rattle loudly inside. There’s a plastic slide on the top, which has open, closed, and permanently locked positions. It does not hold the safety caps, just the pen needle itself, which means you have to use the serrated teeth at the edge of the hole to help you unscrew it into the container and then awkwardly shove it in.

The first one worked fine, but I didn’t like it. The second one locked itself closed forever in my pocket while on vacation, rendering itself useless with only a few needles in it. The third one opened itself in my pocket more than once — the final time, it dumped out three used needles, which I discovered by jabbing my finger into one of them. The fourth and fifth ones were thrown into the recycle bin that evening.

The Ugly

I found a clipper by MediCool, $15 each. Similar to, but uglier and mechanically more awkward than the SafeClip, it claims to work for both syringes and pen needles. But the clipper is, unnecessarily, recessed deeply behind a narrow plastic hole — 4mm needles don’t even reach it. I grabbed the Dremel and slowly, awkwardly ground off all the plastic that was in the way. This makes the thing even uglier, but it does work. I can’t really say I’m satisfied, but there may not be a better alternative right now. There are 8.4 million people in the US on insulin and this is the best we get? Come on, free market, do that thing you’re theoretically supposed to do.

I’m now almost done with Trans/Rad/Fem. Like I said, the writing is really compelling and it just makes me want to devour the whole book.

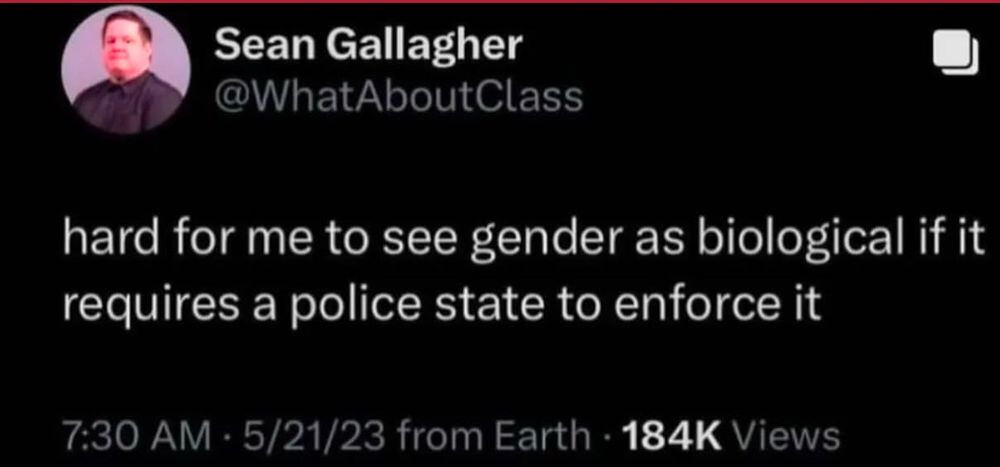

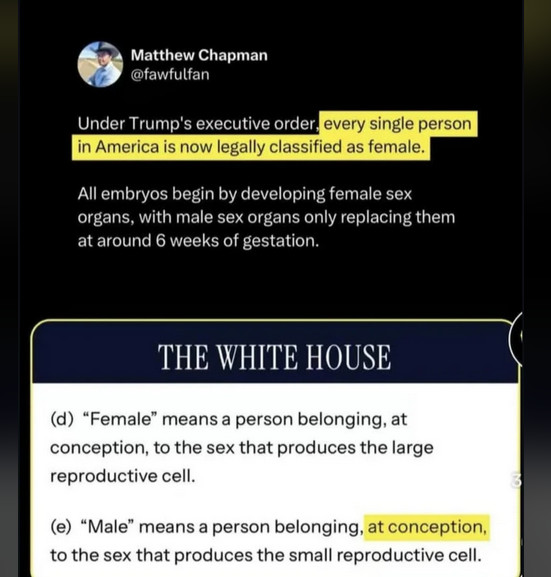

One of the narratives about nonbinary gender is that many cultures around the world recognize(d) more than two genders, and in at least some cases, these people were described as “revered” in some way, often with particular socio-religious roles. And then the colonizers came along, attempted to outlaw them, and caused them to be stigmatized.

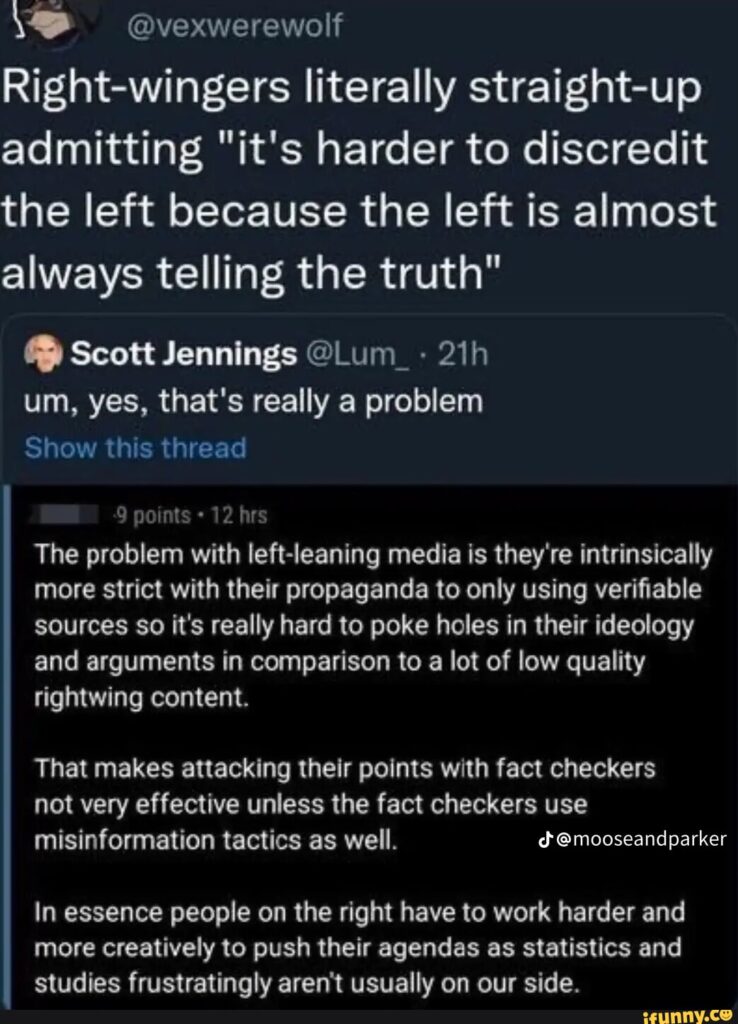

Missing from this narrative — obvious in hindsight after reading this book — is that these cultures tended to be highly patriarchal anyway and that gender-based roles likely should be seen as a red flag rather than privilege.

The author — a trans lesbian from India — says with authority that a majority of the hijra of India are trans women by identity, not nonbinary. It’s just that their society doesn’t recognize them as “real” women, because the only value women traditionally have in India is reproductive. So it shunts them off to a third gender instead — and does the same with intersex people as well as some cis women who are unable to conceive. They live together in communities in abject poverty, and their “special” roles are dancing at weddings (where this isn’t forbidden because their “barren” state might infect the bride) and sex work. And this was true before the British colonization of India. (This doesn’t absolve the colonizers of anything.)

In other cultures, it’s not necessarily the case that counting trans people as a separate gender is inherently anti-trans — but it’s not necessarily not the case either. So, maybe let’s not use cultures that we don’t understand as a model for how ours should be.

Scythians for example. They had a class of priests, born male, who were treated with estrogen extracted from horse urine and considered a separate gender. There were also apparently trans men who were warriors. But this is also a culture that treated women as property of the king, who loaned them to male warriors to be their wives and servants.

This has been why I don’t use the term “sekhet” from Ancient Egyptian either for myself or any of the nonbinary gods of my religion. We don’t really know what the word implied in Egyptian society. Probably not “eunuch” as early archeologists assumed because there’s no evidence of castration, but that leaves a lot of possibilities and not all of them are good.